The EAC is alive and well, no need for a vote

Mr Charles Njonjo, Attorney General of Kenya in the Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi administrations, is very much alive and still lives in the 1970s.

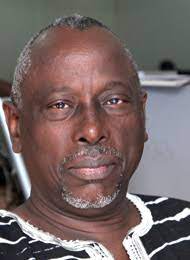

Joseph Rwagatare