Even though African writing existed before arrival of foreign influence, in manuscripts of earlier civilizations discovered, the modern African writer is the one who learnt western languages and tried to articulate a genuine African voice in the face of many masquerading ‘African’ voices by western writers often taking the cover of travel writing.

Even though African writing existed before arrival of foreign influence, in manuscripts of earlier civilizations discovered, the modern African writer is the one who learnt western languages and tried to articulate a genuine African voice in the face of many masquerading ‘African’ voices by western writers often taking the cover of travel writing.

Thus the first popular African books were basically books of freedom that fused traditional oral story telling methods with western craft into a different type of new literary art.

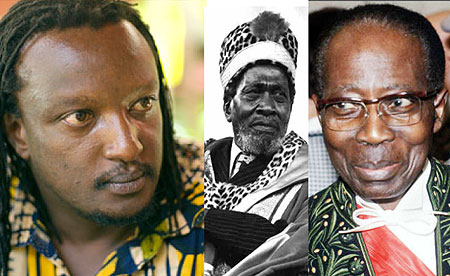

In the early part of the 20th century, a writer was viewed as the voice against oppression. There was a very thin line between politicians, writers and teachers. In 1948, Leopold Senghor published the first anthology of French-language poetry written by Africans, before he eventually became president. Ngugi Wa Thiongo began to write against colonial expression in Kenya and after independence in 1963, continued to criticize the post-independence governments, which earned him harassment and exile.

The likes of Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Taban Lo Liyong were also political critics. Because most post colonial political leaders were ideological intellectuals they also cemented their struggles with books. Jomo Kenyatta wrote Facing Mount Kenya, while Nelson Mandela wrote Long Walk to Freedom.

Writing was about staking the claim for African writers, much less about money. That generation which cherished reading and writing eventually gave way to one that read textbooks to pass exams, and resorted to popular western fiction. Fiction from the older generation sold more in western capitals than in Africa.

The writing arena changed when a new brand of young revolutionary writers who did not identify with the independence struggle arrived. They wrote not in British English but in the lingua franca of the day - sentences and phrases that resulted from morphing of English and local African dialects in the slums and schools.

Now Nigeria’s Chimamanda Adichie from Nigeria has earned herself comparisons to Chinua Achebe. Kenya’s Binyavanga Wainaina won the Caine Prize and started a literary magazine in Kenya that has achieved global recognition. South Africa’s Niq Mhlongo has created waves with his book Dog Eat Dog, based on his experience as a young South African in the post-apartheid era. These new voices of young Africans have shown that Africans can compete favourably with the best of the world of writing.

Africans and specifically Rwandans have a new opportunity to put pen to paper to show the world the real Africa, not the one demonized by western media that portrays poverty, civil war, disease and corruption. Award winning Adichie’s first book Purple Hibiscus was about a fifteen year old in a wealthy Nigerian family that lives under tyrannical oppression and religious fanatics of their respected father. It does not concentrate on taking sides but showing the small family conflicts of religion, modernity within the big picture of political uncertainty.

Binyavanga Wainaina, in his famous satirical essay called How to write about Africa, says "In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates.”

Wainaina tries to show how western writers produce books about Africa which fit the above explanation and the stereotypes promoted by western media. Ronald Elly Wanda in Writers and Development in East Africa argues that it is our task to construct a history that we can claim is ours, one that positively identifies the character of Africa in its present age.

Africa’s new writers are also making it big. A 19-year-old Nigerian undergraduate student Chibundu Onuzo, has just signed a two-novel deal with the British publisher Faber. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie won the 2007 Orange Prize for Fiction for "Half of A Yellow Sun” while Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, published her first novel, "I Do Not Come To You By Chance,” last year, which garnered several awards, including the Commonwealth Writers Prize. In 2009, Uwem Akpan’s debut collection of short stories "Say You’re One Of Them,” which had a story based in Rwanda was picked by Oprah Winfrey and included in her book club, instantly topping the U.S. bestseller list.

However; African writing is still dominated by West and Southern Africa and to a lesser extent Kenya. The recent Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Fiction, which was won by Nigerian Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani had 15 books each nominated from Nigeria and South Africa, a few from Kenya (none of which made the shortlist). Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda did not even submit one book.

Yet one who is spooked by the writing bug need not wait for a writing revolution to hit a country or region. Good books are written by determined individuals and so are many Rwandans. The advantage of living in the above regions is that there are many fora for marketing good writing, but the world today is hungry for new writing from new places.

Good writing should be able to stand on its own, not on the literary strength of a country, and therein lies the challenge for aspiring Rwandan writers.