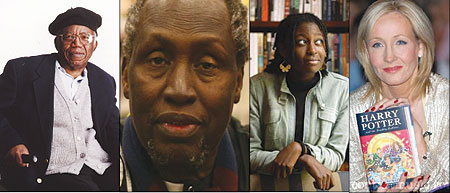

A struggling single mother, Joanne Kathleen Rowling was travelling back to London on a crowded train when the idea for Harry Potter simply fell into her head. According to her website, to her immense frustration, Rowling didn’t have a functioning pen and was too shy to ask anybody if she could borrow one.

A struggling single mother, Joanne Kathleen Rowling was travelling back to London on a crowded train when the idea for Harry Potter simply fell into her head. According to her website, to her immense frustration, Rowling didn’t have a functioning pen and was too shy to ask anybody if she could borrow one.

So she sat and thought, for four hours, and all the details bubbled up in her brain, and this scrawny, black-haired, bespectacled boy who didn’t know he was a wizard became real. That evening she began to write ‘Philosopher’s Stone’, the first of the famous Harry Potter’s Series.

Today, seven Harry Potter’s books later, Rowling’s net worth is $1 billion, a "rags to riches” life story, in which she progressed from living on welfare to multi-millionaire status within five years.

Helen Oyeyemi almost committed suicide but her depression helped her write her first book that was wildly successful. She was born to teacher parents in Nigeria but her family moved to London when she was 4.

Living on a council estate and discouraged from socializing with local kids, she read precociously and played with Chimmy, her imaginary friend, who "died”, hit by a car when Oyeyemi was 9. Helen showed disruptive behaviour in school and suspensions and bouts of clinical depression culminated in an attempted overdose of pills at 15.

After time spent with relatives in Nigeria, she began The Icarus Girl and by her ninetieth birthday, she had earned a book deal with her first few pages, writing it while her parents assumed she was wrestling with A-level coursework.

They didn’t even know she was writing it until she told them she had signed a two-book deal with Bloomsbury for a reported £400,000 advance.

According to the London Evening Standard, she lied to a literary agent that she had written 150 pages of the book when she had just 4 pages. "I signed the contract on the day I got my exam results,” says Helen. It is a testament to her ability that she could write an extraordinary debut novel in six months, get three As with minimal revision, and be accepted at Cambridge.

Arguably, Africa’s most famous writer, Chinua Achebe was born in 1930, in Eastern Nigeria. His family of six children belonged to the Igbo tribe. Representatives of the British government that controlled Nigeria convinced his parents to abandon their traditional religion and follow Christianity.

Achebe was brought up as a Christian, but he remained curious about the more traditional Nigerian faiths. Achebe was unhappy with books about Africa written by British authors like Joseph Conrad, because he felt the descriptions of African people were inaccurate and insulting.

Conrad’s Heart of Darkness projects the image of Africa as "the other world,” the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality.

While working for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation he composed his first novel, Things Fall Apart (1959), the story of a traditional warrior hero who is unable to adapt to changing conditions in the early days of British rule. By the mid-1960s the newness of independence had died out in Nigeria, as the country faced the political problems common to many of the other states in modern Africa.

The Igbo, who had played a leading role in Nigerian politics, now began to feel that the Muslim Hausa people of Northern Nigeria considered the Igbos second-class citizens. Achebe wrote A Man of the People (1966), a story about a crooked Nigerian politician.

The book was published at the very moment a military takeover removed the old political leadership. This made some Northern military officers suspect that Achebe had played a role in the takeover, but there was never any evidence supporting the theory.

Closer to home, Ngugi wa Thiong’o was born in Kiambu, Kenya as the fifth child of the third of his father’s four wives. As an adolescent, he lived through the Mau Mau War of Independence (1952-1962), the central historical episode in the making of modern Kenya and a major theme in his early works.

Ngugi burst onto the literary scene in East Africa with the performance of his first major play, The Black Hermit, at the National Theatre in Kampala, Uganda, in 1962, as part of the celebration of Uganda’s Independence. One of the novels, Weep Not Child, was published to critical acclaim in 1964; followed by the second novel, The River Between (1965).

The year 1977 forced dramatic turns in Ngugi’s life and career. His first novel in ten years, Petals of Blood, painted a harsh and unsparing picture of life in neo-colonial Kenya.

The same year Ngugi’s controversial play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), in an open air theatre, with actors from the workers and peasants of the village. Ngugi was arrested and imprisoned without charge.

It was at Kamiti Maximum Prison that Ngugi made the decision to abandon English as his primary language of creative writing and committed himself to writing in Gikuyu, his mother tongue and since beomc ea household name in global literary circles.

In prison, and following that decision, he wrote, on toilet paper, the novel; Caitani Mutharabaini (1981) translated into English as Devil on the Cross, (1982).

Most successful books have varied stories behind them, mostly ordinary events that would otherwise pass without further mention. Books are about ordinary simple life - real life, they do not come from the stars or the heavens.

Stories in books are everywhere around us. We live them, we see them we hear them, we experience them. Only a few are brave to dream them and put pen to paper.