Shortly after Nyiramavugo III Kankazi Radegonde became Queen Mother of Rwanda in 1931, her brother, Chief Kayondo summoned her, but she counter-summoned him instead, saying she is no longer an ordinary person like him.

"Ntabwo nkiri Umututsi nka we,” which loosely translates to "I am no longer Tutsi like you anymore,” was her response.

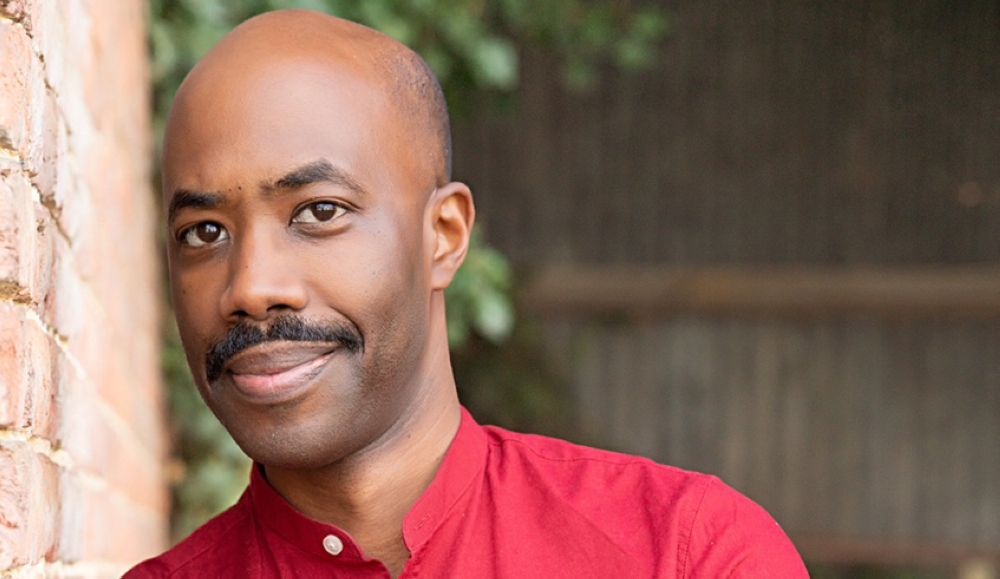

Dantès Singiza, a Historian at the University of Gent and the University of Liege in Belgium, believes this conversation is part of what shows that the terms Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa were pre-colonial social classes, but not ethnic groups.

On November 12, 93 years ago, the vice governor of Ruanda-Urundi, Charles Voisin proclaimed the deposition of then King of Rwanda Yuhi V Musinga, also announcing on the same day that his son, Rudahigwa, would succeed him.

This move further weakened Rwanda’s national unity that was already deteriorating since colonialism began. Musinga was deposed because of his resistance to Belgian colonisation. On his successor’s throne, history records heightened rates of ethnic hatred that eventually led to the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi.

In this conversation, Singiza discusses with The New Times’ Glory Iribagiza different colonial policies and myths that divided Rwandans and why it worked.

Below are excerpts;

In what ways did the Belgian colonists represent Rwanda’s diversity?

When the colonists arrived in Rwanda, they decided to classify Rwandans among three groups, which are Hutu, Tutsi and Twa. In reality, these were nothing but social classes.

Rwandans instead belonged to 18 clans, which were inherited at birth. They included Abasinga, Abanyiginya, Abakono, Abagesera, Abega and more. But the colonists found this too complicated for them to track, because there were around 1,440 lineages related to them. I took time to count all the lineages that were branched out from every clan, and that is the number I got.

Examples of lineages include; Abahindiro, Abagaga, Abamanuka, Abenegitore, Abakagara, Abagagi, Abakongori, Abahenda, Abagereka, Abacumbi, and more, and were based on different people who were great in history. Someone could be a Munyiginya of Umuhindiro, for instance.

It has to be noted that this research was done by Antoine Nyagahene, and all I did was count them. The Bagesera had over 100 lineages, and the Banyiginya had 138 lineages. Other clans had many lineages too.

In what way did they present ethnicity in Rwanda?

The three social classes in Rwanda were dynamic, but the colonists, based on certain racial hypotheses that were popular in the 19th century, and decided to say they were ethnic groups, to facilitate their rule. They believed in biological hierarchies, and so their policies were based on it.

The Twa were below everyone, the Hutu were in the middle, and the Tutsi were on top. They profiled every one of these groups; their physique, mental capacity, and economic standing.

Why is it believed then that Rwanda’s royal family was "Tutsi”?

This is the wrong way to look at it. When the king was crowned, he was no longer part of the social classes. He was therefore not even Tutsi. He was the king of all Rwandans.

In Kankazi’s discussion with her brother Kayondo after he summoned her, she says: "I am no longer Tutsi like you” (the exact reply is: "Ntabwo nkiri Umututsi nkawe: yego navutse i bwega, ariko nashatse i bwami! (I am no longer Tutsi like you. Yes, I was born in the Bega clan, but I married in the royal family” (Source: Mgr Bahujimihigo Kizito, Mutara III Rudahigwa: Uwatuye u Rwanda Kristu Umwami)).

This conversation is one of the examples that shows that the royal family were not ordinary people. The Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa, were really the masses.

Do you think Belgian colonists exaggerated the Rwandans’ diversity?

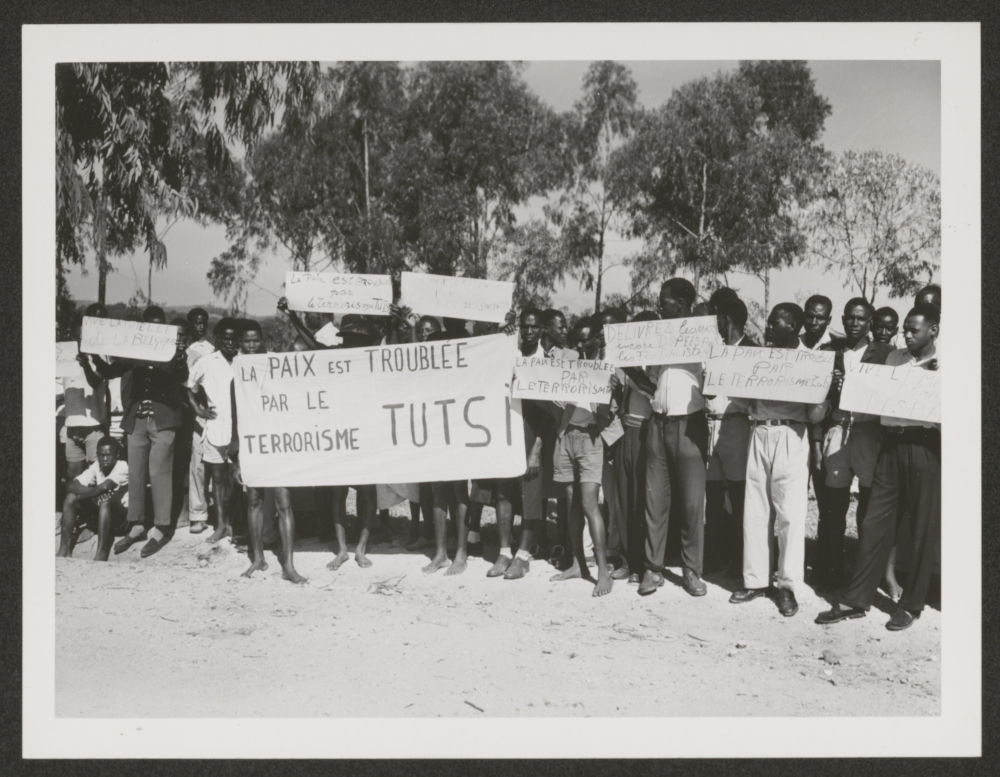

Definitely! They tried to prove that Rwandans were totally different from each other, and the first tool they used was the Identity Card, where they put the supposed ethnic groups in writing.

At this point, the social classes were made ethnic groups, where one belonged until they died, and it would also affect their children. Usually, people would always graduate from one class to another depending on how their economic status changed.

They also created stereotypes on each of the groups, including one’s height, where a Tutsi person was to be from 176 cm tall and above, whereas a Hutu would be 167 cm tall and under, and 150 cm tall and under for a Twa. They also made measurements on people’s noses and other parts of the body.

They wanted this to look scientific, so they used the Pignet Index (indice Pignet), which was suggested by Maurice–Charles–Joseph Pignet, who was a French army doctor. The results would determine what group one would be placed in. For instance, for someone to be identified as a Hutu, it was 0, for someone to be classified as a Tutsi it was 14.

However, even this was not authentic. Some people who shared both mother and father sometimes found themselves in different groups. There are some famous cases in history.

Another stereotype was on mental capacity, where they said that "the Twa are similar to the monkeys they hunt in forests”. They said they were always jumping up and down and didn&039;t have much going on.

They said the Hutu threw around words as they thought them, and that the Tutsi were hypocrites and unpredictable. This was their psychosocial "analysis”.

In politics, which caused much uproar, they said that both Twa and Hutu were "absolutely incapable of ruling.” Instead, they said, the Tutsi were "born to rule.”

Furthermore, they started myths about how the three groups had come to live in Rwanda. They used the Hamitic hypothesis as well as the mythe de l'immigration bantoue (myth of Bantu immigration).

What were the effects of this classification?

Exclusion was the first effect. The colonists said they would work with the Tutsi in political matters because apparently, they were were born leaders. This excluded those who fell in the Hutu and Twa categories.

In education, some subjects were only reserved for high class Tutsi, and others were strictly for Hutu. For example, the section of Administration had two parts; one which would train future chiefs and another to train clerks. For one to attend the former, they would first be evaluated on what ethnic group they fell in and how powerful their family was. Children born from Hutu and low-class Tutsi families would only be admitted in the latter.

Also, a Tutsi would be taken to veterinary school while a Hutu would go to Agronomy school.

What other harmful policies were implemented on the basis of the supposed ethnic groups?

When colonialism started, taxation was introduced. However, a new tax policy was issued on the Belgian rule. There were three major forms of tax; a poll tax, which was given by a male adult who is not disabled. There was also a cow tax, paid by people who had cows that are not infertile, bulls or calves that haven’t made six months yet. Another was the "additional” tax that was paid by people married to more than one wife.

A Hutu man only paid the poll tax. A Tutsi man paid the poll and cow taxes, but if both were polygamous, they paid the additional tax.

Another policy was forced labor, referred to as ‘akazi.’ This was strictly done by Hutu, and never Tutsi. Any person who skipped even a single day would be fined, but also whipped ‘ikiboko’ eight times on the buttocks, without clothing.

Ikiboko is a type of whip made from a hippopotamus hide. Some say one whip peeled the skin off of the subject.

Akazi included road construction, quarrying, cutting and carrying timber to build churches or schools, and more. Everyone had to bring their own tools and had to work 60 days per year (five times a month). Towards the end of colonialism, Akazi had become 120 days per year (10 days per month).

Akazi was also not done by disabled men, elderly men, women and children.

The conglomerate of akazi, taxes, exclusion from public office, schools, and more, is where the hatred between Rwandans began.

Imagine, the Hutu were doing forced labor, and Tutsi chiefs were supposed to supervise. If a colonial administrator passed by and for instance, saw someone taking a break under the tree, he would first punish the chief or the subchief, then tell the chief or the subchief to whip the Hutu for being "lazy”. This created hatred.

Was there any difference between the Belgian and German colonists’ presentation of Rwanda and Rwandans?

Yes, there is a big difference. Germans came to Rwanda before the Belgians. in 1907, there was a big caravan that included scientists who came to study Rwanda on many aspects.

One of them was an anthropologist called Jan Czekanowski, who in his reports told the Germans that Rwandans do not see themselves in the supposed ethnic groups, but rather in 18 clans. He even described the groups as social classes. Later, he also described that Rwandans had a nationalist spirit after interviewing various random people from different parts of the country then.

The Germans somehow saw Rwandans as Czekanowski reported, but they didn’t have much time to focus on how to rule Rwanda because they had to prepare for WWI- which they lost and left.

They also didn’t interfere much in Rwandan politics. However, they introduced the poll tax in 1913.