Growing up in a refugee camp, I was told we were there because my parents, being Tutsis, fled Rwanda to escape persecution by Hutus. As I grew older, I wanted to understand more about this history.

I turned to books written by colonial scholars and found a familiar narrative: Rwanda was first settled by the Twa, followed by the Hutu between the 5th and 11th centuries, and then the Tutsi in the 14th century.

Seeking clarity, I spoke with Rwandan elders, and what they shared was markedly different from what I had read in colonial texts.

These scholars divided siblings into Tutsis and Hutus so effectively that all Rwandan kings were labelled as Tutsi and some presidents as Hutu.

This categorisation became the accepted truth, not just within Rwanda but globally, due to the colonial narrative crafted by European scholars under the guidance of the colonisers.

Today, suggesting that Rwanda's kings (Tutsis) and some labelled Hutu presidents share ancestry might sound irrational. But that’s precisely what this article explores — an ancestral truth that colonialism distorted and nearly erased.

As James Baldwin once noted, we must "go back to where we started, or as far back as we can, examine all of it, and know whence we came."

The loss of identity under colonial influence

It’s challenging today to disassociate from the labels of "Hutu" or "Tutsi," as colonial educators instilled these identities thoroughly.

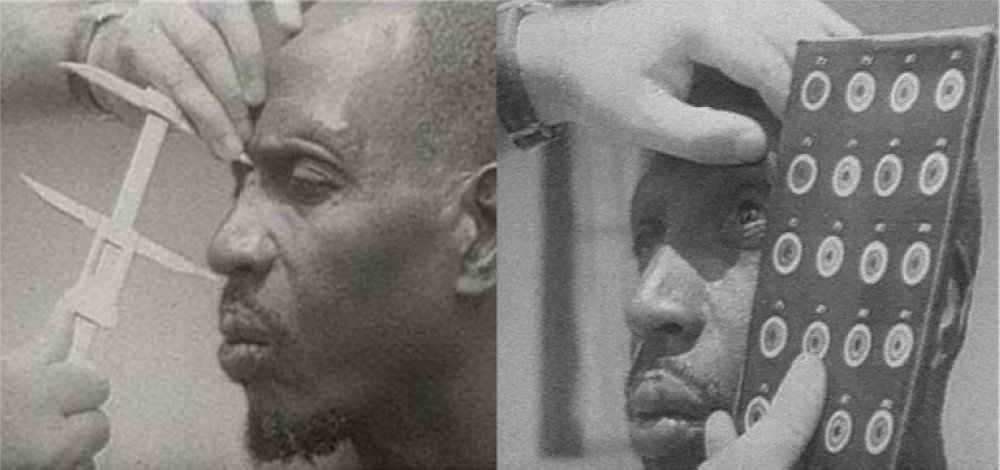

The colonial agenda was to reshape Rwanda into a society that had forgotten its lineage. Before sending anthropologists and historians to Rwanda, Belgian authorities devised a strategy to change the very identity of Rwandans.

Colonial-era scholars were sent to implement the "faire l’homme noir du Rwanda oublier ses ancêtres" project — to make the Rwandan people forget their ancestors.

They succeeded to a degree, convincing us that a former Rwandan president, an Umwungura, was Hutu, and that all Rwandan kings before him were Tutsi, even though they shared the same ancestry.

In order to sever Rwandans from their heritage, the colonisers reinterpreted stories from our oral literature, assigning different groups to various mythical ancestors.

They labelled some Rwandans as settlers under names like Sabizeze and Gihanga, while others were deemed "natives” from Kabeja, who supposedly lacked a traceable lineage.

For those who read our article "Debunking the Myth: The True Origins of Ibimanuka and Abasangwabutaka in Rwanda,” Kabeja’s true legacy is vastly different from the colonial depiction.

Rewriting History through false lineages

Belgian-sponsored researchers, including Georges Sandrart, Léon Delmas, Jan Vansina, and Marcel d’Hertefelt, were effective in distorting our past, especially regarding ancestors.

However, our elders retained their memories of their heritage, providing a chance to trace our ancestry authentically.

The lineage of Abungura exemplifies how the colonial project erased identities. The Abungura were integral to Rwanda's history long before the so-called "arrival" of Tutsis.

Oral history recounts that King Yuhi I Musindi fathered a son named Rubunga with a servant. This son, Rubunga, became part of the royal court and introduced the "ubwiru” — a royal ritual that became foundational in the kingdom.

To obscure Rubunga’s lineage, colonial historians crafted a story claiming he was a custodian of wisdom from the Barenge, alleging that he stole this wisdom for Gihanga.

But historical accounts show that Gihanga was well-acquainted with the Barenge, even marrying into their family.

The colonial scholars’ objective, however, was not historical accuracy but making Rubunga a native through his association with the Barenge, specifically through the figure of Kabeja.

Some colonial sources even claimed Rubunga descended from the Abatege, ignoring that he held the role of the kingdom's ubwiru guardian precisely because he was a direct descendant.

Fortunately, many elders have preserved the true story of Rubunga’s lineage from King Yuhi I Musindi.

The Fabrication of "Hutu” and "Tutsi”

For those still uncertain that the Hutu and Tutsi designations were colonial constructs, consider this: even former President Juvenal Habyarimana shares an ancestral line with Rwandan kings.

His genealogy traces back to Rubunga, son of King Yuhi I Musindi, and ultimately to Gihanga, Rwanda’s founding ancestor.

Meanwhile, colonial projects rebranded Habyarimana as Hutu, while labelling all kings before him as Tutsi, despite their common Basindi heritage, meaning descendants of King Yuhi I Musindi.

In our next instalment, we’ll delve into the original meanings of "Hutu” and "Tutsi” before colonisation imposed these identities.

In Kinyarwanda, we can say, "ubwoko twatsindiriwe butari ubwacu” — we were forced into these labels, which are not our true heritage.

For now, stay blessed and connected to our shared Rwandan identity.