In the years following the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi , a new generation of Rwandan diaspora has emerged, some of whom are the offspring of those involved in the genocide. Among these groups, Jambo ASBL, based in Belgium, has gained notoriety. The name "Jambo," derived from the Kinyarwanda word for "the Word," alludes to the Gospel of John in the New Testament.

In John 1:1-3 and 1:14, it is written: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind...The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth."

ALSO READ: Crimes in a broader phenomenon of scriptural manipulation

This passage, which speaks of the divine nature of Jesus Christ, was perversely co-opted by the genocidal ideologues to lend an air of sanctity and inevitability to their actions. By using the word "Jambo," they sought to equate their own words and actions with divine authority, thereby justifying their poisonous ideology in the eyes of their followers. This foundational Christian concept underscores the truth and salvific mission of Jesus Christ, who embodies grace and truth.

For believers in Christianity, the term "The Word" in this context carries connotations of ultimate truth, divine revelation, and the transformative power of God&039;s message to humanity. It stands in stark contrast to any form of deception or falsehood, highlighting the moral and ethical implications of how words and communication are used in society.

The appropriation of "Jambo," a term imbued with positive connotations of dialogue and understanding, for purposes that include genocide denial, is deeply troubling. It represents a stark divergence from the ideals associated with the Word in the Gospel of John, which advocates for truth, light, and life.

By using "Jambo" to cloak its mission, Jambo ASBL engages in a form of moral and ethical subversion. The organization’s activities contradict the principles of truth and illumination symbolized by the Word in the Gospel of John. Instead of promoting understanding and reconciliation, the misuse of "Jambo" serves to obscure the reality of the genocide, thereby contributing to a continuation of division and misinformation.

Words carry immense power. They can heal or harm, illuminate or obscure, unite or divide. The ethical responsibility associated with the use of words, especially in contexts of historical significance and human suffering, cannot be overstated. The appropriation of "The Word" by Jambo asbl highlights the critical need for vigilance and integrity in how words and communication are employed.

In a world where words can be used to obscure reality and perpetuate harm, Jambo ASBL's use of the term "Jambo" is emblematic of a broader strategy to sanitize and legitimize their genocide denials message by wrapping it in the cloak of religiosity and intellectualism. By invoking scripture, they attempt to reframe the narrative of the genocide, casting doubt on the established historical record and seeking to exonerate their predecessors — Kangura and RTLM.

Rwanda’s religious fabric and Kangura’s appeal

In the years leading up to the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi, the Hutu extremist politicians and their publication Kangura played a central role in spreading hateful ideology. One of Kangura’s most persuasive strategies was the manipulation of religious language, which deeply resonated with Rwanda's predominantly Christian population. By framing its toxic messaging in terms of divine will and religious duty, Kangura made it difficult for ordinary Rwandans to resist or question the calls for violence, rendering many complicit in the atrocities. It is important to explore how Kangura used religious imagery and biblical verses, particularly on the theme of unity, to promote Hutu extremism and hatred of the Tutsi.

Religion has always been central to Rwandan life, with an overwhelming majority of the population identifying as Christian — predominantly Catholic and Protestant. This made biblical references and religious language highly influential. Verses like Psalm 133:1, which states, "How good and pleasant it is when God’s people live together in unity,” and Ephesians 4:3, "Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace,” were widely known to Rwandans and often invoked in churches. Kangura skillfully twisted such verses to equate Hutu unity with moral righteousness and survival, while vilifying the Tutsi as enemies of God’s people.

ALSO READ: The hypothetical son of Hitler: Defending the indefensible

For instance, Issue No. 16 of Kangura, published in May 1991, carried the headline, Ubumwe bw’Abahutu niyo mizero yabo (Hutu Unity is their only hope). The article claimed that the only way Hutus could protect themselves from extermination by the Tutsi was through solidarity, presenting this as a moral imperative. This idea of unity — a central biblical principle — was weaponized to sow fear and division. Instead of promoting peace and cooperation, Kangura distorted the notion of unity into a tool for ethnic exclusion and the justification of violence.

Sanctifying Hutu ideology and the deification of President Habyarimana

In one of its most infamous pieces of propaganda, Kangura issued a set of "Ten Commandments for the Hutu,” a document that became a manifesto for ethnic division and hatred. The tenth commandment read: "The 1959 social revolution, the 1961 referendum and the Hutu ideology must be taught to every Muhutu and at all levels. Every Muhutu must spread widely this ideology. We shall consider a traitor any Muhutu who will persecute his Muhutu brother for having read, spread, and taught this ideology."

The explicit invocation of Hutu "ideology” as a sacred doctrine to be disseminated, much like religious teachings, was particularly effective. The Bible says: "Christians should be ready to share the gospel at all times and in all circumstances.” 2 Timothy 4:2. In Mark 16:15: Jesus tells his disciples to "go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation". And, in Matthew 5:16: Christians are called to proclaim Jesus with their words and deeds. Just as Christians are instructed to spread the Gospel, Hutus were urged to spread the message of Hutu supremacy. This distorted version of evangelism sanctified Hutu nationalism and legitimized violence against anyone — particularly Tutsis — perceived as undermining this ideology.

This commandment directly reversed biblical verses that accentuate the inherent dignity of all human beings, regardless of ethnicity or background. Galatians 3:28, for instance, states, "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Yet Kangura’s version of unity was exclusionary, promoting Hutu solidarity only at the expense of the Tutsi.

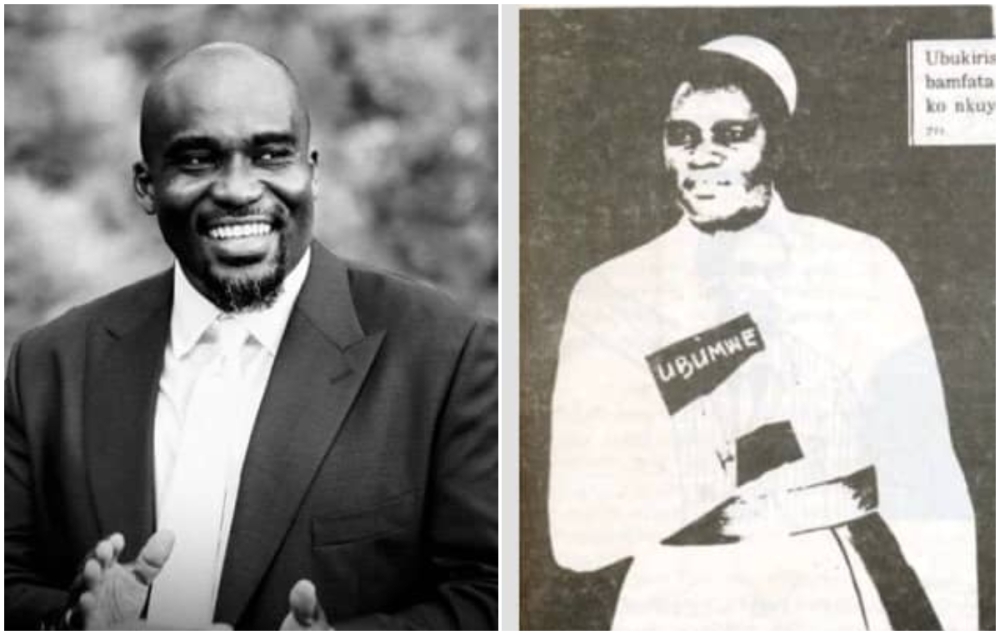

In Issue No. 25 of Kangura, President Juvénal Habyarimana was depicted wearing a bishop’s chasuble and mitre, with the word "Ubumwe” (Unity) emblazoned across the cover of a book supposedly a Bible. This image sent a powerful message that Habyarimana was not only the political leader of the Hutu, but also their spiritual guide. It blurred the lines between political and religious authority, suggesting that opposing Habyarimana — or the idea of Hutu unity — was akin to disobeying divine will.

Habyarimana himself had earlier reinforced this religious imagery in his speeches. At the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND) Congress on April 28, 1991, he spoke of the need for Hutu unity, framing it as a defense against the return to "slavery” — a thinly veiled reference to Tutsi rule. In his September 1991 speech, he encouraged opposition parties to unite against the RPF, which he equated with the Tutsi. This framing positioned the Tutsi as enemies of the Hutu, invoking biblical narratives like those in Exodus, where God’s chosen people — the Israelites — escaped from the oppression of the Egyptians. The subtext was clear: just as God liberated the Israelites from slavery, Hutus must unite to prevent their subjugation by the Tutsi.

The beatification of Habyarimana was further entrenched by broadcasters on the infamous Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM). After Habyarimana’s assassination in April 1994, RTLM announcers, including Valerie Bemeriki, portrayed his death as a sacrilegious act, suggesting that the Blessed Virgin Mary had declared him "our father.” Bemeriki said, "They killed the father for no good reason, for the Blessed Virgin Mary said recently that he was in fact a father, that he was our father, that she had received him.” This religious framing elevated Habyarimana’s death into a martyrdom, galvanizing the Hutu population to avenge his death by slaughtering the Tutsi.

God’s alleged protection of Hutu and Tutsi as heretics

Kangura repeatedly portrayed Hutus as a divinely chosen group, protected by God from the existential threat posed by the Tutsi. In Issue No. 17 of June 1991, the front cover proclaimed: "If it was not for the God of Rwanda who is always on the alert, the Hutu would be in great danger.” This messaging framed Hutu solidarity as part of a cosmic struggle, with divine intervention safeguarding them from their enemies. By invoking God’s protection, Kangura justified violence against the Tutsi as part of a larger heavenly plan, encouraging the perception that the Tutsi were a threat not only to the Hutu, but to the will of God.

This religious manipulation subverted biblical teachings about God’s love for all humanity. Matthew 5:44 instructs Christians to "love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you,” while Leviticus 19:18 calls for forgiveness: "Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself.” Kangura disregarded these teachings, instead promoting fake Tutsi enemies and a theology of hate, exclusion, and violence.

Kangura also used religious language to vilify the Tutsi, portraying them as heretics and enemies of the faith. In January 1992, the magazine published a cartoon depicting a conversation between Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and St. Joseph, discussing how Hutu unity could be achieved. By inserting Christian divine figures into political discourse, Kangura implied that the struggle against the Tutsi had spiritual significance. The Tutsi were not just political adversaries but religious outcasts, akin to those who rebelled against God in biblical narratives.

This perversion of religious language resonated with many Rwandans, for whom the teachings of the church were central to their lives. It echoed the anti-Tutsi sentiment that had been festering in Rwandan society for decades, giving it a spiritual validation. The implication was that failing to oppose the Tutsi was akin to betraying one’s faith — a powerful motivator in a religiously devout population.

The use of religious language in Kangura and other extremist platforms had devastating consequences. By presenting violence against the Tutsi as a religious duty and Hutu unity as divinely ordained, Kangura blurred the lines between faith and politics. Ordinary Rwandans, many of whom were deeply religious, were drawn into the genocidal machine, believing that they were fulfilling God’s will by participating in the atrocities. The publication’s blending of Hutu nationalism with religious language made it difficult for many Rwandans to resist the genocide’s calls, as opposing the violence felt like opposing their faith.