The University of Rwanda (UR) has a new Vice Chancellor (VC), the third in less than three months. The previous substantive VC held the post for a little over one year. A new Deputy Vice Chancellor responsible for strategic management and administration has also been appointed.

Change of leadership of institutions, including universities, is of course, not unusual. It happens all the time for different reasons. For instance, on completion of a contractual term.

But it can also be a reflection of the state of the institution and the thinking of its owners if the change happens midterm. In that case, the changes may be triggered by any number of other factors.

It could be a response to a leadership not quite in tune with the demands and aspirations of the times. Or one mired in internal disputes and unable to resolve or rise above them. Or simply the search for new direction, injection of pace, and therefore the need for fresh, innovative and more responsive leadership with a vision for tertiary education in the 21st century.

What is happening at the UR is not different from what happens at other universities, or indeed, other institutions across the world. Whatever drives leadership changes there reflects the nature and role of the university.

Universities have what might be called a dual and contrary personality. They are at once conservative and revolutionary, traditional and forward-looking, disruptive and constructive. And other tendencies in between.

Their administrative and scholarly communities espouse one or the other, often with great passion and intransigence.

Inevitably, this dual nature will lead to clashes, each wanting to assert its supremacy.

Traditionalists, for instance, who usually occupy senior positions and have connections in high places (or claim to), insist on having things done the way they have always been done. They dismiss innovation as "new-fangled ways”.

Progressives on the other hand are often impatient with the pace of things, even direction, and want change to happen faster. They are contemptuous of traditionalists whom they regard as being caught in a time-warp and therefore obstacles to progress, and would sooner have them shunted aside.

Clearly, managing these contradictory tendencies and creating a harmonious blend and get good results requires a very skilful administrator. He must be one who recognises the other nature of the university: as a crucible of ideas where they are mixed and ground into a great mixture of knowledge that drives progress. Or a workshop where they are hammered and moulded and refined into tools to drive society forward.

Obviously a fair amount of disruption is required. But equally, a similar amount of conservation. To consolidate before the next disruption.

The effective manager will have to possess the ability to create the necessary balance.

There is another factor that will test the ability of a university administrator. Academics, like other celebrities (they are stars in their respective fields), have enormous egos. They tend to want to go their different ways and can be very difficult to manage, indeed can be disruptive.

Some claim a sense of exceptionalism because of their special expertise or singular achievements which they want everybody to recognise, and will not easily bend to authority.

On the other extreme, there are the very sensitive type, often very brilliant, but also fragile and insecure and need support and encouragement to perform to their highest potential.

Others claim godfathers among the country’s political leadership and use that to intimidate colleagues and gain some unfair advantage.

All these the university’s top officer must contend with and manage appropriately – handle big egos without giving in to them, put braggarts in their place without hurting too much their air of self-importance, and encourage brilliant but shy minds to produce their best without appearing to be patronising.

Then there is the perpetual question of funding for which answers must be sought. For some reason, they remain elusive.

These are general observations about universities. They may or may not pertain to the University of Rwanda.

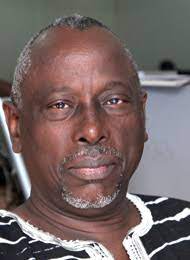

Still, Dr Didas Kayihura Muganga, the new Vice Chancellor of UR, has his work cut out. He has to manage the university as the custodian of knowledge and tradition, and also as the creator of new knowledge and centre for innovation, as an institution of the present but more importantly of the future.

To do that successfully, it is not enough that he is an accomplished academic, although that is obviously an advantage. He must also be a leader and have the mindset of a CEO of a large and successful business.

It is a tough assignment, but he must surely be up to task. That must be the reason he was tapped for it. Still he needs everybody’s support.

The views expressed in this article are of the writer.