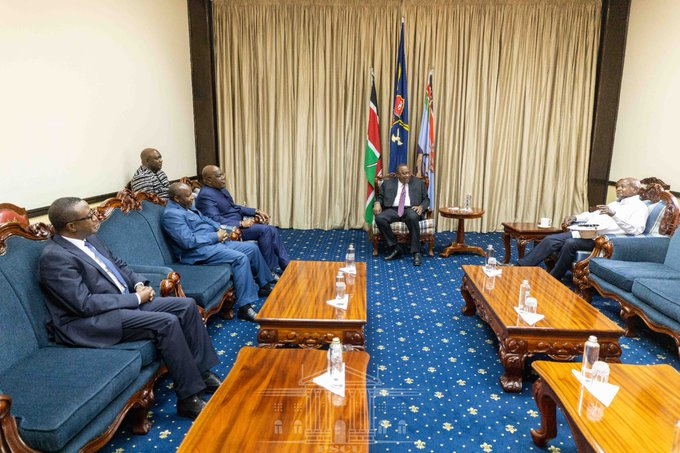

When leaders from five East African Community (EAC) partner states met in Nairobi on April 21 for the second Heads of State Conclave on DR Congo and subsequently came up with what appeared to be concrete resolutions, some saw it as the latest in a series of decades-long failed agreements and missed opportunities.

President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya, who’s serving his last months in office, had convened the Conclave in his capacity as the current EAC chair.

The leaders resolved that a regional force shall be formed "immediately” and deployed to the Congo to take on negative forces that would reject calls to disarm.

They also demanded all Congolese armed groups to "participate unconditionally in the political process to resolve their grievances” if they’re to avoid military action.

The leaders of Burundi, DR Congo, Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda (represented by the Foreign Affairs minister) also demanded all foreign armed groups operating on Congolese soil to "disarm and return unconditionally” and immediately to their countries of origin or be "considered as negative forces and handled militarily by the region.”

At the same time, it was announced that Kenya would host an inter-Congolese dialogue designed to find a political settlement to the rather protracted crisis.

But then the situation on the ground deteriorated fast and Kinshasa started to cherry-pick the armed groups it wanted to talk peace with, reducing some to non-existent or just proxy groups.

Fast forward, this week, President Uhuru said he had agreed with his counterparts that it was time to set up and deploy to Congo the proposed regional force.

The EAC chair has since invited military commanders from the partner states to a meeting in Nairobi on Sunday to finalise preparations for the joint deployment.

Given the current context and previous experiences it’s understandable that some people will be pessimistic about this initiative.

However, it should be recalled that this is the first time that EAC would be moving as a bloc to intervene in Congo’s near-endemic conflicts and instability.

Importantly, the fact that DR Congo is now an EAC member should serve as an opportunity for the region to reach a consensus on the best way to deal with the security threats.

Together, member states of the EAC, and indeed the wider International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), have what it takes to make a notable contribution toward pacifying the eastern DR Congo.

However, this can only be possible if there is sufficient political will, particularly on the part of Kinshasa, to genuinely work with all partners to find a sustainable solution.

As such, Congo’s recent decision to integrate genocidal FDLR and other extremist elements linked to the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda in its army can only worsen the situation further. So are its unfortunate decision to double down on its baseless allegations of Rwanda’s support for the M23 rebels and actions designed to escalate tension with Kigali.

It’s only through a credible, inclusive and informed process that Congo’s war-torn east can finally be pacified and allow for its citizens to live in peace and harmony again, and to join hands with their counterparts across EAC and ICGLR to foster integration and sustainable development.