In a previous column, I explored the concept of Ndi Umunyarwanda—a bond meant to heal wounds inflicted by a distorted history. We discussed how Rwandans historically identified themselves as Ndi Umunyarwanda w’ Umugesera, w’Umuzigaba, w’Umucyaba, w’Umusinga, w’Umwega, w’Umunyiginya—not as w'Umuntu or w’Umututsi.

This identity of Ubunyarwanda was systematically dismantled by colonial powers who sought to rewrite Rwanda’s history. To erase the true story of our origins, colonial scholars fabricated a narrative centered around Sabizeze, who was said to have descended from heaven under the name Kigwa.

Kigwa and his companions, the Bimanuka, were portrayed as meeting Kabeja, the King of the Basangwabutaka.

The colonial agenda required one Rwandan to be cast as a divine stranger and another as the rightful landowner. This constructed dichotomy, which cast the Ibimanuka as Tutsis and the Abasangwabutaka as Hutus, destroyed the oral tradition of Ubunyarwanda.

Consequently, Rwandans began to see themselves through the lens of this imposed identity, leading to the gradual erosion of the concept of Umunyarwanda.

In just a few decades, the colonial narrative took hold, replacing Ubunyarwanda with divisive identities. The result was that people who once saw themselves as brothers now identified as Batutsi—the privileged, so-called invaders—and Bahutu—the underprivileged landowners.

Pierre Smith, in his book La Forge de l’Intelligence, along with other colonial anthropologists and historians, played a crucial role in perpetuating this narrative.

Smith claimed that Muntu was Kigwa’s son, who was the son of Nkuba, and Nkuba was the son of Shyerezo, a king of heaven.

Marie Rose Mukarutabana, in her essays, argues that this misconception stems from a misinterpretation of Rwandan symbols. She states that Muntu should be seen as a symbolic figure akin to Adam in biblical tradition or Manu in Hindu tradition—representing early mankind, not an individual king of Rwanda.

Oral history supports Mukarutabana's view, suggesting that Muntu was among the first people to inhabit Rwanda, not a divine figure. According to Smith, however, Nkuba (the thunder) begat Kigwa (the fallen one), who begat Muntu (human being), and so on.

But oral history clarifies that Sabizeze was the son of Sabiyogera, and his mother was Nyamwezi—a woman from the west, possibly from present-day Tanzania.

The Belgians attempted to obscure this truth, pressuring King Yuhi V Musinga to accept that Rwanda originated from Gasabo rather than Mazinga. King Musinga, however, insisted that Rwanda’s true origin was Mazinga.

Sabizeze’s journey, as recorded in Rwandan oral history, tells us that he came from Buha bwa Ruguru (in today’s Akagera National Park), bringing with him tools and animals to survive in a dense forest.

At that time, no other humans were present. He married his half-sister Nyampundu after a disagreement with Mututsi, who refused to marry her because she was his direct sister.

This marriage established Sabizeze as the leader of the first settlers in what is now Rwanda. He was known as Umwami w’inyoni n’inyamaswa—the king of birds and animals—because of his isolated existence in the forest.

In his book Zigzag à travers le Grand Lacs, Bishop Julien-Louis-Edouard-Marie Gorju described Rwanda as a dark forest before Sabizeze’s arrival. Gorju's account, written before the colonial distortion of Rwanda’s oral history, supports the narrative that Sabizeze did not encounter other human beings upon his arrival.

The claim that Sabizeze met King Kabeja is a fabrication. Kabeja is said to be the grandfather of Nyamususa, Gihanga’s wife. It’s clear that Sabizeze could not have met Kabeja, as the latter wasn’t even alive at the time of Sabizeze’s arrival.

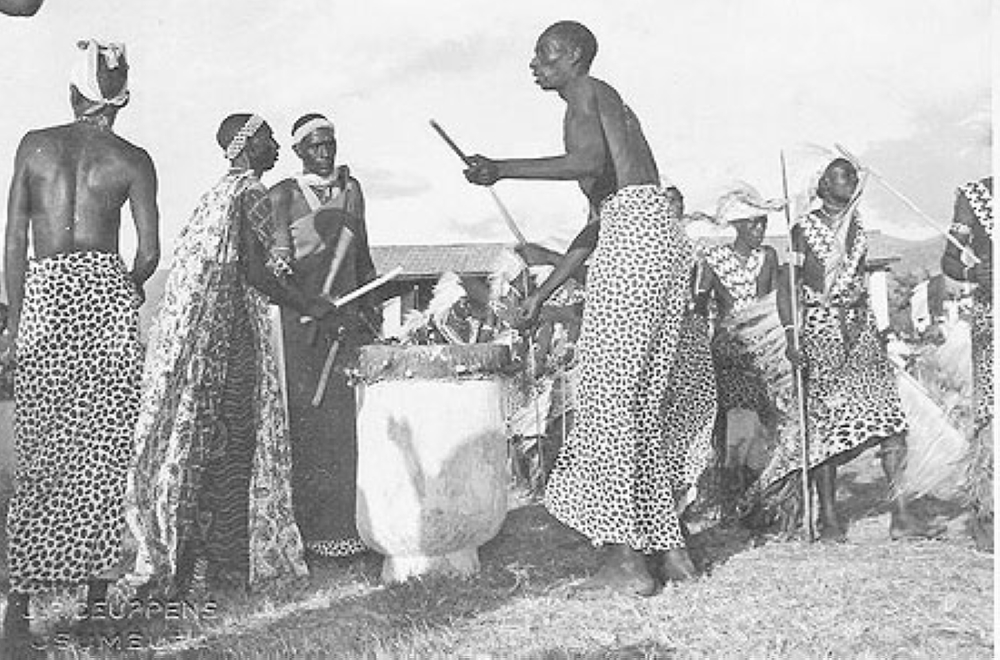

This colonial distortion has caused significant suffering and hatred in Rwandan society. Below is a summary of Sabizeze’s story as told by Rwandan elders.

Nyamwezi, a woman from Bungeringeri, was married to Sabiyogera, who had several wives. Unable to bear children, she consulted a seer and eventually gave birth to Sabizeze.

After her death, Sabizeze was mistreated by his stepmothers, leading him to leave his father’s home with his half-brother Mututsi and half-sister Nyampundu. Together, they traveled from Buha bwa Ruguru to Mazinga.

In Mazinga, Sabizeze and his companions lived in isolation, their animals multiplying while they remained the only human inhabitants. Sabizeze eventually married Nyampundu, and they had many children. Mututsi, who initially refused to marry Nyampundu, later married their daughter Sukiranya after moving to the opposite hillside.

This story reveals that Sabizeze and his companions did not descend from heaven, Egypt, or Ethiopia but from Ubuha bwa Ruguru—modern-day Tanzania. Furthermore, there were no other people present when they arrived, contrary to the colonial narrative.

The fabricated story of the Abasangwabutaka will be the subject of our next issue.

Until then, stay blessed.