IN 2019, Celine Uwineza, a survivor of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, published a book, "Untamed”, a tale about her life as a 10-year-old, who during the Genocide saw her mother being shot in the leg, and together with her family seek refuge in convent in Kicukiro.

Her life took a drastic change three days later when she witnessed the Interahamwe militia kill her mother and her three siblings, while she narrowly survived death, later on she reunited with her brother and father.

The book also shares her healing journey, decades later after the Genocide, from PTSD.

She describes her state of mind during the three months period of the Genocide as traumatic, lost, confused and lonely.

In the book, Uwineza shares pictures of her lost family members and relatives as she shared her memories of them.

"My goal is to highlight the importance of memory preservation as a tool to fight against genocide ideology and violence. The book is also an opportunity to recognize Rwandans’ journey of healing, resilience and courage,” the author told The New Times prior to the launch of her book.

Besides the book, Uwineza together with her brother and father have, with the help of video footages, documented memories of their family members that were killed during the Genocide and shared it on YouTube titled "Our family story #Kwibuka.”

For many, pictures are more than mere visuals, but memories of their loved ones that they cling onto.

Born in Kamonyi District, Southern Province, Cyril Ndengeya was 10 years old when his sister, father and uncles were murdered.

They were killed before he and his remaining family quit their birthplace in Rukambura Sector and fled to former Mugina Commune where they got rescued by RPF-Inkotanyi.

The pictures that Ndegeya keeps with him takes his memory back to the best moments that he spent with his slain relatives.

"Every time I see these pictures, especially during the commemoration period, they help me keep in touch with them even if they are not here physically,” Ndegeya said.

"Whenever I look at these pictures, I remember vividly when the pictures were taken and I get mixed feelings. I feel bad that I can’t share such moments with them anymore but the pictures also put a smile on my face when I remember the moments we had together,” he added.

Ndegeya regrets that he only has a few of his lost relatives’ pictures while he could have kept plenty of them had he been aware of the importance of pictures in preserving the memory.

"I was too young to know how important pictures are. Had I known, I would have collected all the pictures of my family and kept them with me,” he shared.

The 37-year-old says pictures are so important because they always bring back detailed memories, including when the pictures were taken.

As a photographer who now knows the value of a picture in creating memories, Ndegeya plans to use his professional skills in photography and document all the photos of his family relatives and those of his birthplace, especially how it looked like after being destroyed during the Genocide against the Tutsi.

"I thought I would start documenting those pictures this year, but the situation is too tricky to successfully reach everyone who I expect to help me find those pictures. But I still have that in my mind because I want to have them documented digitally to prevent them from getting too old and fading away,” he said.

While many survivors cling on to their loved ones’ pictures, sadly there is a section of genocide survivors whose pictures of their killed relatives were among the properties destroyed.

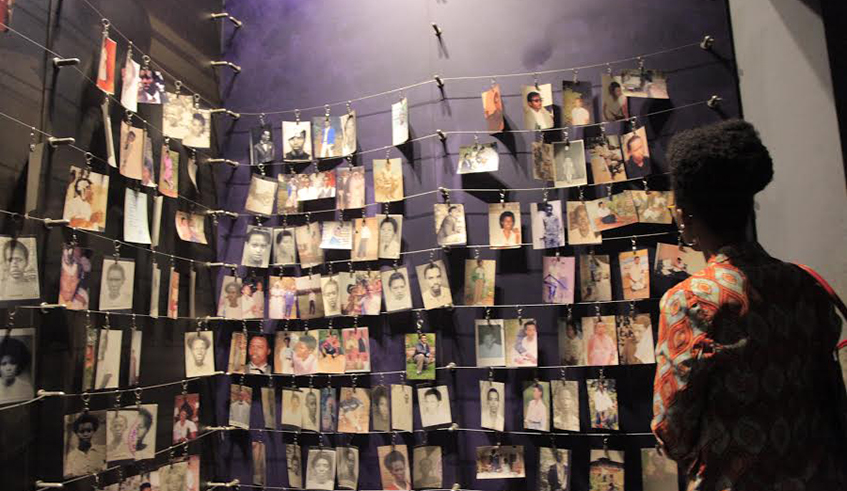

Some genocide survivors also chose to preserve pictures of their deceased loved ones at Genocide memorial sites.

Serge Rwigamba is one of the long time -serving guides at Kigali Genocide Memorial (KGM), in charge of visitors’ engagement.

Rwigamba often sees how the faces of people change when they get to see the photos displayed at the Genocide Memorial.

He shares some visitors can be seen speaking to the pictures while others get visibly emotional.

He believes that photos have the power to connect the dead with the living.

"When people pay a visit at Genocide Memorial, they not only stare in nostalgia, but also feel their loved ones when they touch those images,” Rwigamba told The New Times.

"These aren't actually just "Photos ". They are people who left them in a more drastic way. So photos keep memories alive,” he added.

With the current generation now dominated by visuals, pictures and films will be the future of educating the world about what happened in Rwanda in 1994.

It is through the pictures that female author Karen Bugingo, known for her book ‘My Name Is Life’, found the power they have in preserving the memory when she once visited the Genocide memorial, only to find herself stuck with images displayed inside the memorial site.

"Pictures have played a very big role in preserving the memory of the Genocide against the Tutsi in my heart. I personally relate more to pictures while learning because those images are stuck in my head,” Bugingo said.