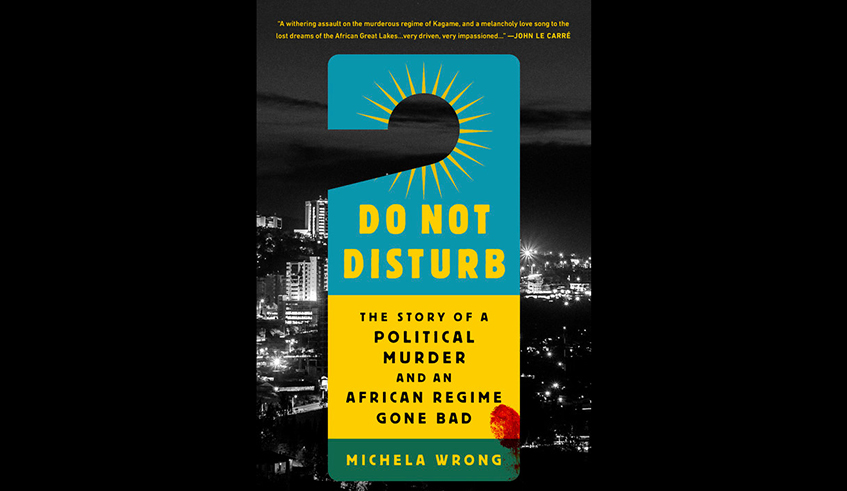

A number of recent books on Rwanda have been written by journalists. The latest of these is Do not disturb by Michela Wrong.

Journalists usually write short stories about events and places of current interest. But when they have been at the job for some time, they also write books.

The best of them are well-written, easy to read, interesting and even persuasive, and a useful record and reference. With these, there can be no quarrel.

The worst are little more than crass propaganda or apology for fringe viewpoints and groups, or hate-filled tracts. With this sort, we take issue.

Most appeal really as thrillers, tales of adventure or personal accounts, not as deep or profound analyses of the situations they describe.

This is not surprising, given their trade. In their daily business, journalists report on events at which most of us are not. They give us an eye-witness account of those happenings for us to get a sense of the picture, and for this use the most vivid descriptive language in their coverage.

But do not be deceived: no reportage is ever disinterested. Every reporter has a bias and wants to persuade readers to share it, but more often, to impose it. And so this type do more than reporting.

They interpret the events for us, select what we must see and know, and for this choose the most emotive words, most eye-catching description and spectacular incident to influence our attitudes. Another word for this is sensational.

When some of them, especially those who act as publicists for a certain group or interests, write books, they are expanding their interpretation role to more than an event, to a whole society. Their bias is then most blatant.

It gets worse when the story is influenced by a personal agenda or that of others with whom they may have had intimate relations, or the policies of another country.

There is another major weakness in the worst of journalists’ books. In their usual practice, journalists focus on an event at a particular moment and before long are on to the next story. They do not have the time, patience or inclination to see the web of connections between various events, the actors involved and the context in which they take place.

Trouble is they try to turn this limited, short-term impression into an understanding of the entire history and culture of a people. The single incident, the isolated statement, or unusual behaviour then becomes typical of the whole society or offered as an explanation for more complex issues. For them, everything is so simple and straightforward.

They do not recognise the complexity of language, the ironies and nuances in particular discourse, levels and layers of meaning in different situations, and sub-plots or counterplots in various relationships and events. And even when some of these are explained, they can really only have a partial understanding.

Accounts in many of these books are often based on anecdotes, chance encounters in hotel lobbies or cocktail parties, the odd remark by a senior government official sometimes taken out of context, or the personal observation made in passing. These are then generalised as incontrovertible fact about a certain people or country.

As long as these come from so-called dissidents, fugitives in foreign countries, aid workers or diplomats they are deemed credible. Apparently, credibility is measured by the amount and intensity of anti-government sentiment.

They do not question any assumptions behind these utterances, in fact create their own, and then make them fit and validate what it is they are writing about.

And yet, journalists are trained to be sceptical about most things, to question them, never to simply accept what they are told as truth. Where any such exists, it is often not the inquisitive sort, but the kind that passes judgement, especially where Africa is concerned.

And so the writers appoint themselves critics and make their scepticism the standard of judgement. On Africa, this turns into cynicism and contempt, and is in reality a form of racism. Certain achievements are supposed to be beyond Africans, even when the evidence is indisputable. That can only happen if they have violated one thing or another or committed some other terrible crime defined by those writers.

Apparently the more cynical and contemptuous you are about African leaders and people, the more credible you are. In their world. It is wrong, of course, but that is the world of Michela Wrong, Judi Rever and their ilk.

The views expressed in this article are of the writer.