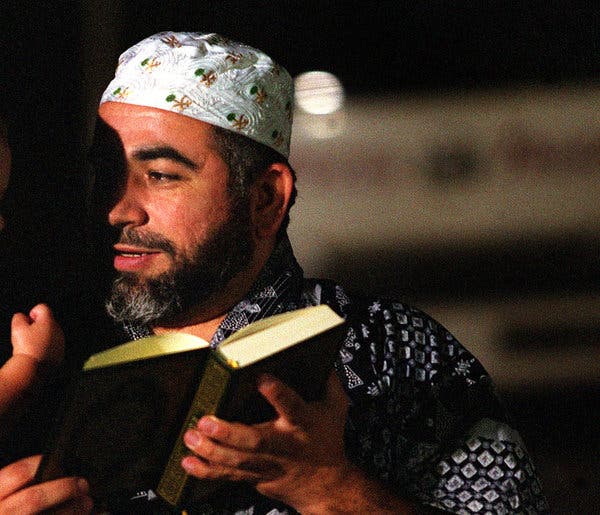

The news at the weekend was about Rwanda taking in a stateless person deported from the United States of America. The man, Amin Hassoun, a Palestinian, was reported to have been living in the United States since the 1980s.

In the wake of the attack on New York in September 2001, although not connected to them, he was convicted and sentenced for sending money to Islamic organisations thought to be linked with terror groups.

The United States was left with a problem after Hassoun had served his sentence and as the law demands had to be deported. He had nowhere to be deported to and could not legally be held any longer after serving his sentence. You see, Palestine is not a state and he had not taken US citizenship.

In comes Rwanda to the rescue and takes in the man.

That alone should not have made big news. Deportation is common, especially in the United States. Nothing exceptional there. Actually, the trend in the west in recent years has been to shut out immigrants and expel those already within. Migration was the big international headache until covid-19 came along and eclipsed everything else.

What to do with migrants was causing tension between and within countries. It was threatening to bring down governments or break up regional blocs, and was responsible for a surge in fortunes of right-wing, nationalist political parties in some countries.

The interest in the story was that Rwanda was bucking this trend and welcoming those that others had rejected. African countries, too, have kept out fellow Africans. But even this should not really be news.

Rwanda has acted this way in the past and the world has actually come to accept, even expect, that this country will not always move with the herd, but that its direction will be determined by carefully thought out choices, one of which is openness to the world.

Hassoun is only the latest to find a home here. A year ago, Rwanda took in African migrants who had been stranded in Libya as they attempted to go to Europe. They were offered several options. They would be here pending a move to a third country willing to accept them. They could return to their countries. Or they could settle here.

Since their arrival, some have already left for Sweden. Others are still waiting. The relocation programme continues but was only interrupted, like everything else, by covid-19.

So offering Hassoun a home is in keeping with Rwanda’s stated policy of open doors. The question that should be asked is why the country continues to go against what everyone else is doing.

Part of the reason is in Rwandans’ experience of statelessness, rejection, wandering and bearing the blame for all kinds of ills in other countries. No decent person would wish anyone to go through a similar experience.

It is also a question of dignity. All the above experiences subtract from the full enjoyment of being human. They are examples of indignity and are intolerable.

The policy extends to Rwandans as well, including those who, for whatever reason, choose to leave the country. They are always free to return and indeed, are encouraged to do so. This is a reversal of trends in the past when this country was a source of outbound human traffic, usually forced, and was closed to the rest of the world.

Accepting people like Hassoun is in another sense an attempt to end the lament and blame syndrome among Africans and act instead. Africans cannot always wait for others to come to their aid first before they do anything about it.

Some of the rich countries now closing their borders against migrants, lure some of them, those with exceptional knowledge or skills, to go and settle there. So there must be some benefits from certain types among them.

Migration is not the only area Rwanda has been bucking the common trend. It has done the same in peacekeeping.

The unwritten manual among peacekeepers has been something like this: Stand as far away as possible from the belligerents. Avoid all danger as much as you can. And while at it, have all the fun, end your tour of duty and go home safely. Where there are riches to be picked, do so. You can even sell your weapons.

Rwandan peacekeepers have a different operational mindset. They do the duty for which they are deployed but go beyond that and add a humanitarian element. They build schools and hospitals, and even provide basic healthcare services. They build roads and provide clean water to citizens.

In the process they have earned the trust of the local population and government where they are deployed, and a good name for their country.

All this is part of a sense of uniqueness that has marked Rwanda this past quarter century. It is not one that the country has actively sought, but rather one imposed on it by history and circumstances, as well as principle and human values.

The views expressed in this article are of the author.