Public health experts recognise health communication as vital to public health programmes that address disease prevention, health promotion, and quality of life. It can make important contributions to promote and improve the health of individuals, communities, and society.

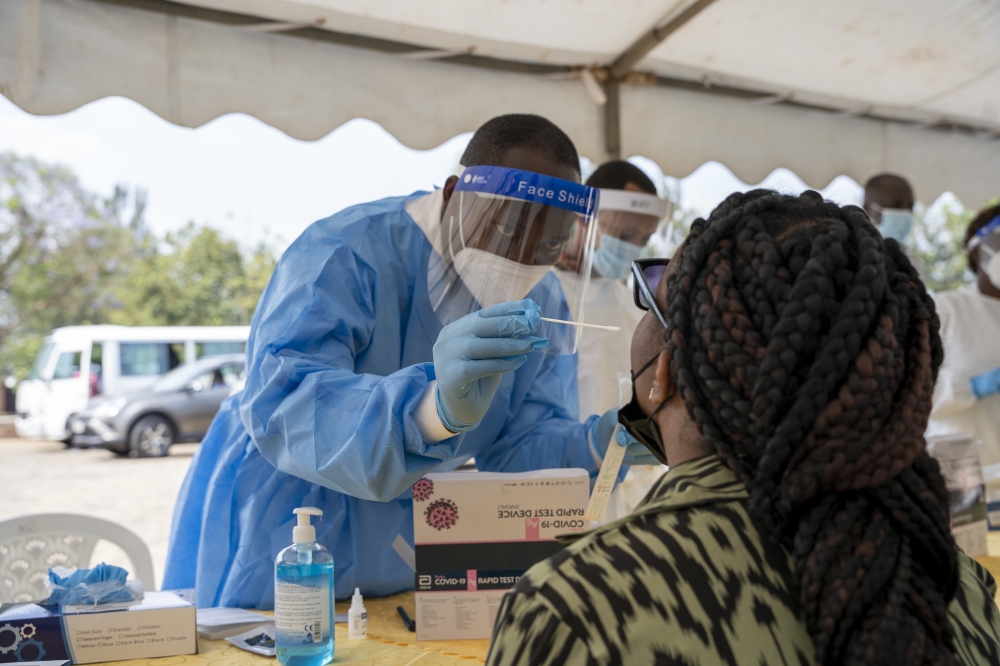

During the Covid-19 pandemic, journalists across all fields became health journalists by default, and scientists were thrust into roles of science communication. As we now face new challenges, such as H5N1 bird flu and outbreaks of mpox, effective communication, and public engagement remain crucial.

Consequently, scientists, particularly those in public health, must develop skills in clear communication and advocacy to navigate these ongoing and emerging health threats.

Misinformation was widespread during the pandemic. I noticed people in my social circle starting to believe in conspiracy theories, and it seemed like misinformation was becoming synonymous with public health messaging itself. Some experts argued that scientists and decision-makers often withheld uncertainties in Covid-19 data and interventions, overstating their confidence. As evidence evolved, public trust may have diminished.

We are living in an era marked by unprecedented levels of misinformation, disinformation, and outright anti-science aggression, where fake news spreads faster than the truth. The public increasingly relies on WhatsApp, TikTok, and social media for information rather than trusted health agencies and scientists.

The WHO even ranks the anti-vaccination movement among the top 10 global health threats. The resurgence of measles and whooping cough outbreaks in some parts of the world in 2024 underscores the severity of this issue.

We also learned, through difficult experience, that even the best scientific evidence can be overshadowed by different agendas and vested interests. It has become evident that good science does not necessarily translate into informed policy decisions.

There is no certainty that well-crafted policies will be effectively implemented. This disconnect highlights the complex interplay between science, politics, and policy, emphasising the need for stronger advocacy and better communication to ensure that scientific insights lead to meaningful action.

Public health practitioners must acquire skills to effectively engage with the public and the media. This includes writing op-eds, giving interviews, speaking at public meetings, and drafting policy briefs for decision-makers.

They should also learn to simplify public health messages, organise campaigns, and utilise social media. Mastering advocacy and diplomacy is crucial, as these skills significantly influence both the public and policymakers. They should also learn about podcasts, narrative storytelling, effective use of social media, planning and execution of advocacy campaigns, strategies to tackle misinformation, how to communicate uncertainty, and about the importance of diplomacy in global and public health.

During emergencies such as global pandemics or natural disasters, effective public health communication and education become vital, as seen during the Covid-19 pandemic when daily press conferences and public health messages were widely consumed.

However, public health messaging remains crucial beyond crises, playing a key role in improving population health and preventing future health disasters. Public health messaging isn’t just important during those times of crisis; it is an essential element as public health leaders work to improve the health of populations and prevent future health disasters.

Fundamentally, public health messengers need to gain the trust of their audience and motivate that audience to do something. This will require being judicious in the actual crafting of the public health message, whether that be part of a social media campaign or through other platforms. Just as a physician’s foremost responsibility is to their patient, a public health official’s foremost responsibility is to the public.

Public health messaging must be clear and concise, with a focus on appealing to both the "heart and the head”, as advised by the World Health Organization (WHO). Effective messages should include a clear call to action and avoid numerous abbreviations, ambiguous words, technical jargon, and complex sentences.

According to WHO, the anatomy of a good public health message includes elements such as appeal, approach, content, text or image, context, and a trustworthy source.

As we continue to effectively communicate public health, we should thoroughly understand the issue, set clear and focused goals, convey solid public health facts, and identify and research the intended audience. We also need to reach out to non-health sector actors such as education, media, transportation, and technology to allow for more comprehensive and effective public health communication.

Dr Vincent Mutabazi is an applied epidemiologist.

X: @VkneeM