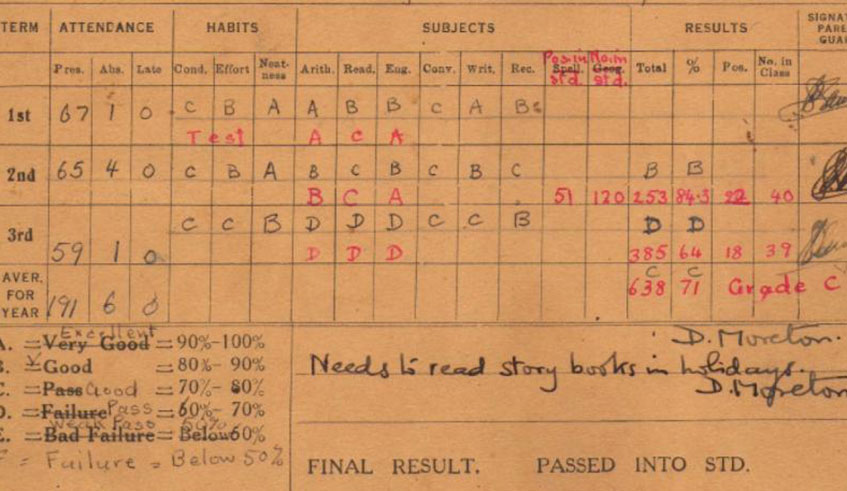

If a student earns grade C in a math test on his report card, is that a good grade, or does this mean he’s the poorest performer in the class?

If you ask for a parent’s opinion on this, then a teacher’s, it is highly likely that you will get contradicting views.

But this disconnect is just the beginning when it comes to how these parties understand the education system and all the grades, terminology and communication within. This is according to sources that spoke to The New Times.

Thamar Mukarugwiza, a mother of two boys in primary school, says parents should be helped in a way that they understand clearly what is in a report card.

A teacher distributing report cards to his students at the end of the term.

"Teachers should be helping out parents in a way that will enable us have that complete, accurate picture of what children are achieving,” she says.

She points out that a report card to parents is the primary and most effective tool through which they know how their children are doing academically. But report cards usually fail to mention if students are performing at grade level.

Conversely, Maurice Twahirwa an education specialist and a primary school teacher at APADET, is of the view that report cards are only the third-most important tool for understanding student achievement. For teachers, a report card is a combination of grades, effort, and progress.

He also says that teachers feel pressure from administrators or parents to avoid giving too many low grades, and some teachers, he reveals, are expected to let students re-do work for additional credit.

"Yes, report cards alone do not measure achievement and do not equate to grade level,” Twahirwa says.

Normally, parents receive their child’s test scores from school every after a term in school. While these scores show if or not students were on grade level or performed highly, they can sometimes be difficult to decipher.

Twahirwa also mentions that there’s a big gap between how well parents think their children are doing, and how well students across the nation actually perform.

Olivier Minani, a teacher at Excella School and an IT expert, says that these contradictions make teachers feel untrained and unsupported, especially when engaging in such conversations with parents.

He says that when they tell parents about their child’s poor grades, some parents blame the teachers.

He adds that some parents are more concerned about the happiness and emotional well-being of their children, while teachers are worried about a student being on track academically.

However, Swaib Musubire, a head teacher at Blue Lakes International School, says there’s also a gap between how much parents think they’re involved in school and how much teachers say they are.

"Parents definitely believe that they are doing a good job being involved, without a doubt, and what’s really fascinating is that teachers see it very differently,” Musubire says.

He is of the view that in order to get parents and teachers on the same page, schools should feel obliged to provide more information about whether students are performing on grade level.

For example, some schools have embarked on using a worksheet they develop that provides information and advice on how parents can help students at home.

Secondly, as a way of improving communication with parents, programmes such as using home visits or "Academic Parent Teacher Teams,” an initiative that allows more time for teachers to meet and collaborate with parents, should be put in place.

editor@newtimesrwanda.com