It is not ‘Gashyantare' (February) yet, but the scorching sun under which Ibihame by’Imana, a celebrated all-male cultural troupe, was rehearsing under felt like it was not for the weak. About 30 men, mostly young danced with so much passion and high energy that one would worry about the ground on which their feet stomped. It was only around 11:00 AM and they still had the rest of the day to go.

Many things stood out about this group. First was the passion in their eyes, the laughter when one of them did something funny, and the fact that they were giving it all their energy- at least so it seemed. I could only imagine how it would sound with ‘amayugi’ (ankle bells), and the sight of them in traditional attire. These boys and men uniformly dance to the beat (kudasobanya in Kinyarwanda).

There is a Rwandan saying that goes "uko zivuze, niko zitambirwa,” which loosely translates to "as the drum sounds, so goes the dance,” and this is what was happening. It may sound obvious to the uninitiated, but the meaning goes beyond music and dance, to how Rwandans related to pre-colonial and colonial leadership.

Drums signified so much more than just being a music instrument. First off, ‘ingoma’ means literal drums, but it also means ‘the reign’. There were also ‘Ingoma ngabe’, which were literal drums, but which signified the monarch and were used for the coronation of kings and their queen mothers.

For Ibihame by’Imana, the drums that sound are danced to in mostly guhamiriza, which is a warriors' parade made of regiments of ‘Intore’ (the chosen ones, the fighters), who used to perform carrying actual weapons. Present-day Intore are not armed, but they carry replicas of spears and shields.

They answer to war-themed calls such as the famous "murakumbure ikotaniro ye”. These calls are code-words that announce what dance pattern they are going to follow, and whoever knows the words can dance along, even if they didn’t train together. They represent fighting tactics that when at the battlefield, the fighters would then know which one to use. Certain fighting and battle scenes are recreated. They are traditionally known as ‘Imihamirizo’.

The polyphonic music of the Amakondera aerophones and drums accompany the Intore dancers to and off the stage. However, there is no 'guhamiriza' without ‘ibyivugo’, which are self-praising odes of war that every man recites in an excited tone. They are supposed to have learnt from a young age to handle weapons and the art of commanding, with the mastery of beautiful words and beautiful gestures. The praises are mostly for cows and talk of greatness, boldness, bravery, fearlessness, and strength. Intore do this while portraying their beauty, grace, and power. And yes, they must smile all through.

Robert Masozera, the Director General of Rwanda Cultural and Heritage Academy (Inteko y’Umuco), told The New Times in an interview that there are about 70 of them (imihamirizo), and they include: 'Ibihogo,' 'Ihembe,' 'Ikotaniro I,' 'Ikotaniro II', 'Imanzi', 'Imparirwashema', 'Indateba', 'Indege', 'Inyambo', 'Urukatsa', 'Urukundo rw’imiheto', 'Ruhame', 'Itanganika', and 'Ingeri'.

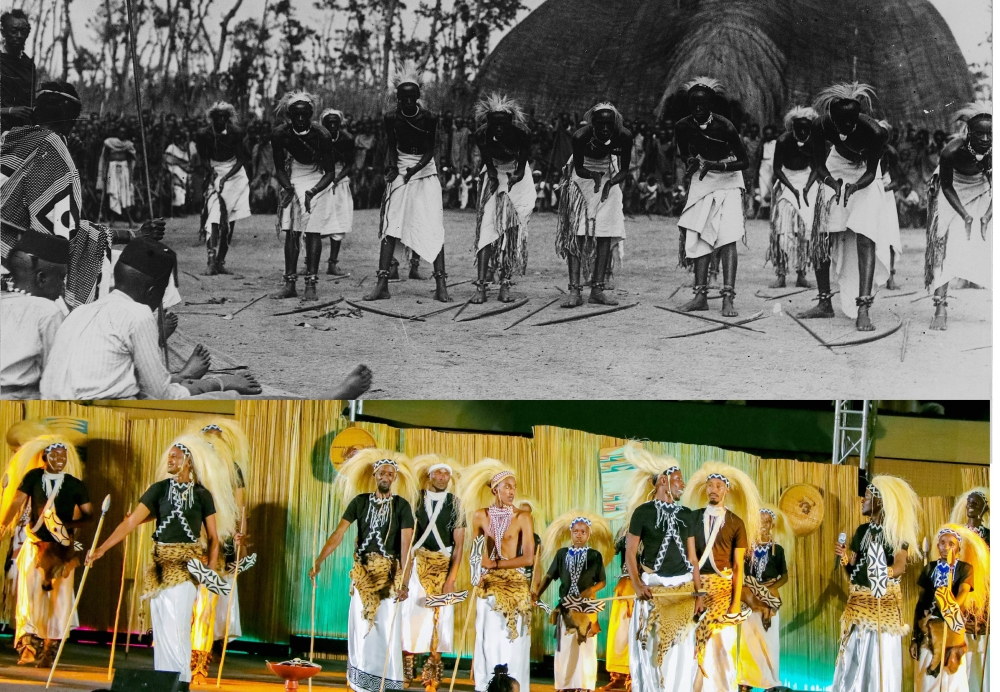

Historically, each Intore troupe was attached to a royal militia, and guhamiriza was an important skill that every boy and man had to own. However, some dancers stood out more than the others, and one of the very famous was the Chief of Mukingo, Frédéric Butera, who was also known as Butera bwa Nturo. He was so famous that he got his photo on a bank note of Congo-Belge during colonialism. He led the Ishyaka troupe and Indashyikirwa II during the reign of Mutara III Rudahigwa.

Guhamiriza gained perfection and prominence in the 19th century, and even more during the reign of Yuhi V Musinga, who ruled Rwanda from 1896 until 1931. Under his reign we see famous troupes such as Chief Rwubusisi’s ‘Inkwaya’. These were known in odes of war as ‘umuheto/imiheto mu byivugo’ and ‘Indatsimburwa mu mazina y’inka’.

There was also ‘Ibihame’, who were Musinga’s troupe. Their name slightly translates to "well acknowledged fighters (or dancers)”. They were also very famous in their time.

In his research titled "Introduction to traditional Rwandan dance,” Jean-Baptiste Nkulikiyinka notes that the arrival of the Belgian colonists marked the dismantlement of the Intore. Nevertheless, the "notables” continued to send their sons to the court so that they received the education provided under previous reigns before they turned to colonial school.

"Thus, dance allows the gesture of warrior heroes to be symbolically perpetuated. It is of all, the more considerable importance as military power was one of the essential cements in the consolidation of the kingdom. The parade dances and poetry draw their inspiration from names with pastoral and warlike connotations,” he wrote.

He also notes that contrary to the conventional guhamiriza, the Hutu Power regime that took after the colonists sought to eradicate any attributes of the monarchy by erasing warlike and pastoral references.

"Thus, in the commune of Masango, dance masters apply to choreographies a vocabulary inspired by new political and social circumstances. The titles invoked no longer refer to bovine or warlike valor but to the referendum (kamaramhaka), independence (indepandansi), or the execration of serfdom (nangubuhake),” Nkulikiyinka wrote.

He adds that the authentic "ancient Rwandan military instinct” is so much so that the old names with warlike connotations partly regained their place.

A new era?

After Rwanda gained independence, guhamiriza was watered down in the country because of financial or political motives. However, its authenticity regained its place in neighbouring countries where Rwandan refugees who fled instabilities since 1959 were living. The acclaimed great Intore include Athanase Sentore who had belonged to Indashyikirwa, King Mutara III Rudahigwa’s troupe. Jean Marie Muyango is one of his students who stood out the most.

Since the late 1950s, all-male troupes that specialized in guhamiriza were extinct in Rwanda, until 2013, when three men; Aimable Bahizi, Olivier Burigo and Emery Igihangange- who were famous Intore in the 90’s when they were refugees- decided to revive the practice.

They founded Ibihame by’Imana, which currently has more than 100 members, and 65 of them will perform in their concert on January 19, 20, and 21.

Edmond Cyogere, a member of the troupe, told The New Times in an interview that their main purpose is to resurrect, restore, and pass on the authentic guhamiriza practice to the next generation, but also to make it regain its popularity.

They could achieve this, given how popular they have become in just a couple of years. Their 2023 concert sold out and hundreds of their fans were unhappy to have missed out- which informed their decision to hold this year’s concert for three days.

Cyogere was quick to note that Ibihame by’Imana does not in any way see themselves as superior to any other troupe, but that they merely do their part in preserving the culture.

"Preserving the culture is our duty, and that is why one of our missions since our foundation is to pass it on to the next generation. It is also every Rwandan’s responsibility to do so,” he noted.

He added that to them, guhamiriza is a way to reconnect with Rwanda’s authentic culture, because every move has a meaning.

For Inteko y’umuco, their role in preserving the authentic traditional dance includes doing research, training troupe coaches, and to partner with different people to train young Rwandans to dance and sing. They also recently published two books on Rwandan traditional dance and music.

It should be noted that however, because of its intrinsic value, many have claimed that guhamiriza should not be associated with dancing, and maybe they’re right.