IT HAS ALWAYS been known that improving literacy requires both community involvement and skilled teachers. Now an impact evaluation report shows that literacy boost was greatest where the two were combined.

IT HAS ALWAYS been known that improving literacy requires both community involvement and skilled teachers. Now an impact evaluation report shows that literacy boost was greatest where the two were combined.

A two-year study, conducted in Gicumbi District from 2012 by researchers from Stanford University (UK), with support from Save the Children, also showed that groups that were subjected to any of the interventions had student skills improve.

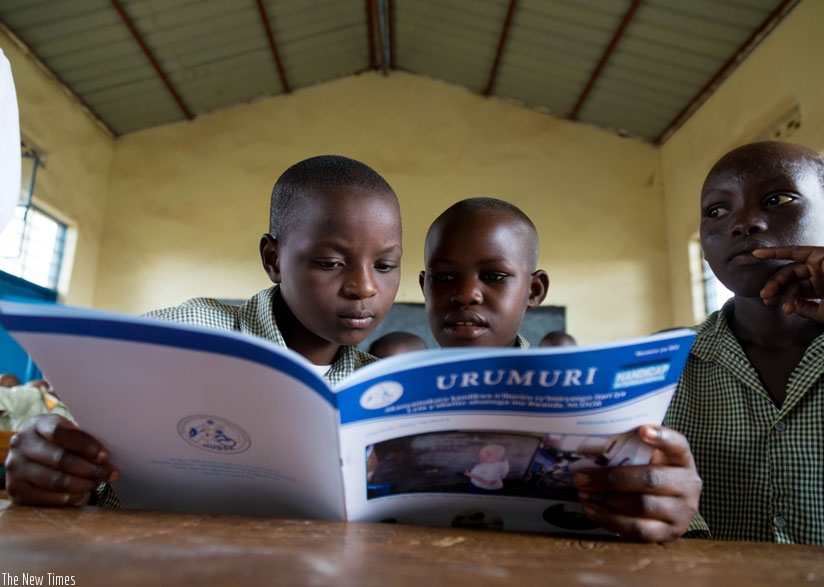

The report, dubbed "Literacy Boost in Rwanda,” studied individuals from p1 to p3 in three test groups namely; teacher training only (TT), teacher training combined with community action activities (LB) and a control group that receive no intervention.

"Overall there was improvement in oral comprehension, reading fluency, reading comprehension and reduced repetition in early primary,” said Claude Goldberg, the principal investigator at Stanford University Graduate School of Education.

By the end of the study, the number of students promoted to P3 had increased by 44 per cent compared to students in the group that received neither of the interventions.

Challenges remain

Despite annual repetition rates being lower in LB or TT, at 37 per cent and 36 per cent, respectively, than in the control group, which had 44 per cent, nearly 2 in 5 students repeated at least one early primary level.

Overall, 31 per cent of students tracked over the period of two years did not meet a basic literacy threshold.

While reading workshops or trainings at community levels were being used to promote literacy, the study found that close to two-thirds of parents do not know that such workshops exist, while 80 per cent of families had no single representative during the entire period of the study.

Only 17 per cent felt these trainings were significant in improving literacy.

Golberg said availability of sufficient reading materials does not necessarily promote the desired degree of literacy in absence of the required support.

"A lot of rich families have books but they do not use them. Books are useless to children without some sort of help from parents or caretakers,” he added.

While several books are published in the local language, some publishers argued that robust measures are needed to address the challenge of parents and communities who shun reading.

"The books are available and many are now published in the local language just to promote reading. The problem is only very few parents will spare some time with their children,” said Jean Nepo Niyitegeka, the managing director of PERDUA Publishers Ltd, in Kanombe.

Globally, 250 million children cannot read and write regardless of school attendance while some 200 million young people finish their school without necessary literacy skills.

editorial@newtimes.co.rw