The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi left Rwandan society in turmoil. Over one million people had been killed. Acts of insecurity persisted, with pockets of interahamwe spread throughout the country.

This is the fifth part of a nine-part series extracted from four of the recently published book, Policing a Rapidly Transforming Post-Genocide Society: Making Rwandans Feel Safe, Involved, and Reassured, authored by the Rwanda National Police (RNP).

The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi left Rwandan society in turmoil. Over one million people had been killed. Acts of insecurity persisted, with pockets of interahamwe spread throughout the country. Hundreds of thousands of people had fled the country along with the defeated regime. Remnants with ties to the fallen regime that had stayed were hostile to the RPF and willing to offer sanctuary to the killers and their weapons as they hunted for survivors.

The new government inherited a devastated country littered with decomposing bodies, destroyed property, and traumatised population in which social capital had been decimated, and lacking most basic needs. This context formed the foundation on which the new political order established itself. It had as its immediate task the restoration of key institutions of the state necessary to establish calm within society.

As the new government consolidated its authority, order began to return. It then set about the task of establishing infrastructure for arresting and trying hundreds of thousands of genocide suspects many of whom continued to pose a threat to genocide survivors. Re-establishing law and order infrastructure, however, had serious problems to contend with, key of which was the state of the justice sector.

All that remained of it after the Genocide were 14 prosecutors, 39 investigators, and 244 judges. Prior to the Genocide, the tally had been 87, 193, and 750, respectively. It was these decimated ranks of judicial officials that were supposed to investigate and prosecute thousands of genocide-related cases.

Similarly, the forces of law and order had to be built from scratch. What had been the primary law and order institution under the Habyarimana government, the gendarmerie, had collapsed along with it. In addition, what was left of the physical infrastructure used for policing purposes had suffered great damage, while equipment had been destroyed. Consequently, there were no functional stations, vehicles, communications equipment, and office equipment. The rest had been carried off to the then Zaire as the remnants of Habyarimana’s security forces fled after losing the war.

Further, given their active involvement in the Genocide, the bulk of the gendarmerie’s officers, at the time the only people with policing experience, had also fled the country. Upon the establishment of the new political order in July 1994, the responsibility for restoring law and order and performing tasks traditionally reserved for the police, rested with the Rwanda Patriotic Army (RPA).

To appreciate the challenges involved, we turn to the recollection by then Sergeant Alice Sebagabo, a gendarme at the time:

"Uniforms were not enough. You would have just one uniform; we didn’t have offices. We didn’t have equipment. We didn’t have paper; we would interrogate people without paper to write on. I would beg for chairs at the commune. Even getting them from the commune was a struggle. I would go to the Parquet to beg them for paper and vice versa. So, the lack of materials was a general problem (ikibazo rusange) for all institutions.”

Former prosecutor Tharcise Karugarama, who served in the court of appeal based in Ruhengeri, which covered the old prefectures of Ruhengeri, Gisenyi and Kibuye, recalls: "After the Genocide, the whole infrastructure in the police and other security agencies was broken. It was important to prosecute genocide cases, and importantly, to re-establish security. In the ministry of justice donors used to give us more than we needed but gave nothing to security organs. If the prosecutor’s office had extra computers, extra chairs, or rims of paper, for instance, these would be given to them.”

The Gendarmerie

The enormity of the demands placed on the military by the addition of new tasks to its primary responsibility of fighting the remnants of the genocidal forces rendered it necessary to establish a police force. Thus, the establishment of the gendarmerie immediately after the RPF seized power was a response to the enormous challenges of establishing law and order in a challenging environment.

The first batch of the new gendarmerie officers came from the RPA. Focus was placed on those who had some knowledge of policing. During the liberation struggle, the RPA had created a gendarmerie unit. Two principle reasons explain its creation. First, by 1993 the rebel forces had under its control a large territory. A military police unit was created to ensure discipline in the rebel force while the gendarmerie unit would handle policing responsibilities in these liberated territories. Secondly, one element of the Arusha accords between the Habyarimana government and opposition political forces called for the integration of RPA officers in the national army, the Forces Armees Rwandaises; under the arrangement some of the rebel forces would join the gendarmerie.

A veteran of the liberation struggle narrates:

"As the peace process gained momentum, we were headed for integration, fighters to be integrated into the army or the gendarmerie. In preparation for integration provided by the peace process, after the Arusha agreement we were supposed to take over a proportion of the command in the army and the gendarmerie. So we had to prepare for that.”

It was these officers who formed the nucleus of the new gendarmerie in post-genocide Rwanda. With time, others, including some from the Habyarimana-era gendarmerie, were brought in, after a rigorous selection process, to expand the size of the force and beef up its capacity. It is from this group that the first post-genocide gendarmerie Chief of Staff, Colonel Deogratias Ndibwami, was selected in 1995, leading the institution till 1997 when he was replaced.

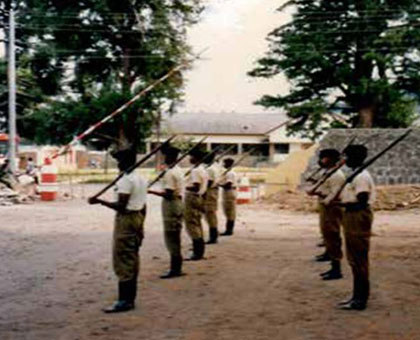

A key imperative the new force faced was to provide common training if minimum standards were to be introduced. According to a report by Lt. Col. De Rover, who conducted an evaluation of the communal police and the gendarmerie in December 4 1995, in the area of education and training, "There is, at the moment, almost no qualified Rwandan instructor available to provide the desired levels of basic and advanced training.” UNAMIR police had provided the initial training starting in August 1994 and lasting three months.

In his speech at the pass-out ceremony for the first batch of 99 gendarmes, on November 5, 1994, then Vice President and Minister of Defence, Paul Kagame laid out what the country expected from the force, cautioning the new officers against treating ordinary people unjustly:

"We cannot tolerate such behaviour because it paints a negative image of the whole armed forces…detractors are waiting to exploit any small mistake, to turn a mole into a mountain so as to ruin our image. Understand that they want to paint the government in negative light and use that to work with the criminals without any remorse.”

It is clear from the vice president’s comments that he believed the conduct of the security forces would be an important factor in enabling the new government to avoid having its name dragged through the mud by detractors looking for the slightest opportunity to do so. A clear break from past practice was needed in both the management of the state more broadly and in the approach to law enforcement.

Policing in Rwanda was to change radically, with the imperative to treat the ordinary person with dignity becoming a central element in its day-to-day activities.

The sixth part will be published on Thursday.