On the morning of April 7, 1994, just hours after widespread killings broke out across the country, thousands of Tutsi started arriving at Ecole Technique Officielle (ETO) de Kicukiro, a former technical school on the outskirts of Kigali City in the now bustling Kicukiro neighbourhood.

On the morning of April 7, 1994, just hours after widespread killings broke out across the country, thousands of Tutsi started arriving at Ecole Technique Officielle (ETO) de Kicukiro, a former technical school on the outskirts of Kigali City in the now bustling Kicukiro neighbourhood.

At the time, the place housed a camp for Belgian peacekeepers under the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (Unamir).

Blood-thirsty militiamen camped outside the school, with all kinds of weapons, ready to exterminate the fleeing Tutsi anytime.

On April 11, the Belgian peacekeepers left despite the refugees pleading with them not to abandon them at the mercy of the killers.

Some even attempted to block the military men from driving out of the school because they considered them their sole hope of survival. The refugees knew their departure meant they were going to be hacked to death with machetes or nail-studded clubs.

However, in response, the peacekeepers shot in the air and drove away, leaving the Tutsi at the mercy of the many Interahamwe militia who had camped there. Of the about 4,000 Tutsi who had sought refuge in the area, only 100 are known to have survived the killings that followed.

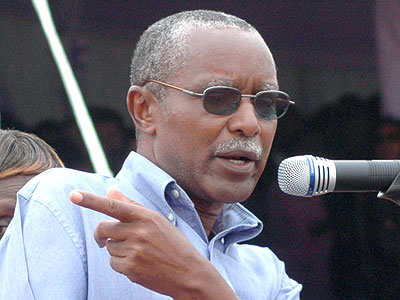

Venuste Karasira, 62, was among the first individuals to arrive at ETO-Kicukiro and watched as his relatives, friends and neighbours were hacked to death. Twenty years later, Karasira returned to the ground where he took refuge in 1994 and where he and the other fleeing Tutsi were abandoned by UN peacekeepers. He told his story to Jean-Pierre Bucyensenge.

Four days after the Rwanda Patriotic Army (RPA) started the liberation war in October 1990, there was an intense shooting in Kigali and government told the public that the RPA had invaded. Many Tutsi were then locked up in prisons as they were labelled collaborators of the rebels. Many died in prison.

Those who survived were released six months later following the N’sele accords. [The N’sele Ceasefire Agreement was signed on March 29, 1991, in Zaire–now DR Congo–between the then government and the Rwanda Patriotic Front, the political wing of RPA. The agreement provided for the cessation of fighting to pave way for negotiations or a final peace agreement.]

Since 1990, there had been a lot of killings everywhere in the country; we lived a traumatised life. But still we had hope that the situation might change because of various reasons like the N’sele accords, Arusha peace agreement, we had the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (Unamir) peacekeepers and as well there were 600 RPA soldiers in Kigali. But, unfortunately, genocide was committed.

The night of April 6, after the death of President Juvenal Habyarimana, was tense. There were heavy gunshots, which meant a lot of killings were being committed. The next morning, roadblocks had been set up and RTLM (Radio Television Libre des Mille collines), which played a very bad influence all along its life, was inciting the Hutu to kill Tutsi who had been branded cockroaches and snakes.

I knew that Belgian Unamir forces were here in this technical school of Kicukiro. I was living at about 800 metres from here. On April 8, early in the morning, my family took refuge in this school.

Panic and fear

When we arrived, we found a lot of people and others kept coming. As people continued to arrive, we tried to organise ourselves. Elderly persons, children and pregnant women were sheltered in classrooms and dormitories. Others remained outside at the playground and we started digging pit latrines for hygiene purposes.

It was a rainy season. But that rain helped us so much because people could tap water droplets from plant leaves for drinking. This school was bushy, and had many trees. We stayed here with a lot of fear up to April 11.

We had a team to contact Unamir peacekeepers for some issues like security and other information. I remember we asked them to inform the RPA soldiers that we are at the school. We believed in those brave soldiers; we believed that they could do something and rescue us. But the Belgian soldiers refused.

In the afternoon of that day, we saw Belgian Unamir forces parking their ammunitions and other belongings.

Left to the militia

We approached and asked them not to leave us in danger, but they told us that our [the Rwandan] gendarmes will protect us. We insisted, but in vain. I remember one of us asking them to give us a few guns so we could protect ourselves...

Desperate, we got children to lie on the ground to barracade their way so that they would not leave us. Do you know what they did in response? They fired volleys in the air and the children scampered away.

The departure of the peacekeepers heralded our tragic moments. Interahamwe militia and gendarmes invaded the school and forced us out, surrounding us up to Sonatubes. They told us to sit down.

Some military officers came and had a short meeting. Finally, a decision was made to take us to a place where we would be protected. At least, that is what they said. While at Sonatubes, we could see other Unamir peacekeepers pass-by in their UN vehicles and other [Rwandan] military officers but no one asked why we were there.

We began our ‘Calvary’ to Nyanza that afternoon. On the way, under heavy rain, people were being killed until we reached Nyanza where we were forced to sit down again and they had yet another short meeting after which one of them asked if among us there were Hutu.

Some went holding their identity cards that were inscribed with ethnic belonging. The killers were then instructed to ‘start the work.’ People were killed using all sorts of weapons until late into the night. We were around 4,000 people but less than 100 survived. Of the survivors, many lost limbs.

Had the RPA soldiers not arrived the next morning to rescue us, no one among the 100 could have survived. We owe these brave soldiers a lot.

Today, we are rebuilding our lives. Of course, the government’s support has been important. We have houses, our children go to school, and we can access medical services and so much more. We thank government for other initiatives, including Gacaca courts, efforts to promote unity and reconciliation, the repatriation of refugees, and, above all, we have peace and security.”