The ongoing trial of Pascal Simbikangwa has revived discourse on the origin of Rwanda’s ethnic groups. Just last week, Jeune Afrique published an article in which historians Jean-Pierre Chrétien and Marcel Kabanda discuss the theory of Tutsi as foreign invaders and a legitimate enemy to be neutralised.

The ongoing trial of Pascal Simbikangwa has revived discourse on the origin of Rwanda’s ethnic groups. Just last week, Jeune Afrique published an article in which historians Jean-Pierre Chrétien and Marcel Kabanda discuss the theory of Tutsi as foreign invaders and a legitimate enemy to be neutralised.

How did this theory come about?

It is important to understand that Rwandans lived together before independence. When the Germans, Rwanda’s first colonisers arrived, they found a highly developed social structure with a King on top of the administrative ladder supported by powerful chiefs with all Rwandans categorised under 27 clans.

These clans originated from various parts of the country and had specific totems. For example, Abazigaba had a leopard for totem, and were found in Nduga, Gisaka, Bwisha, Ndorwa, Mubari, Bufumbira, Rukiga and other places.

These clans were known as "Ubwoko”, a word now associated only with Tutsi, Hutu, Twa.

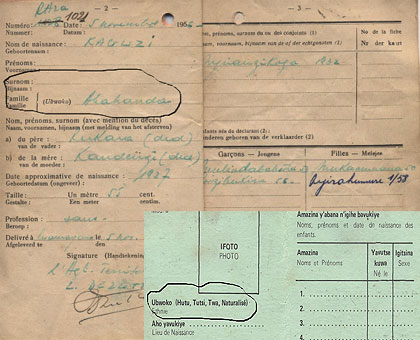

With the advent of the Belgians and identity cards, came the search for an appropriate word to better describe the different groups.

The Belgian identity card equated Ubwoko to family and clan. When distributing the cards, the Belgians would ask, "Uri bwokoki?” (What clan are you from?) and people would answer, "Ndi umutsobe” (I am Umutsobe).

The same identity card also divided these clans along the lines of Mututsi, Muhutu and Mutwa, what the Belgians called "race”. However, given that Rwandans were culturally and linguistically homogenous, this was not the appropriate word.

In Kinyarwanda, Ubwoko refers to race, clan, family, ethnic group, type, or category. There are no distinct words to capture these differences. However, what is certain is that Rwandans before and during colonial times identified Ubwoko with clan.

So what exactly was Hutu, Tutsi or Twa? These were social formations based on a number of things including social class or occupation. You could be Umuzigaba and be either Hutu or Tutsi, under the same totem.

When 27 became three

The new republic born after Belgium granted Rwanda independence, institutionalised and promoted ethnic differentiation. The old identity card was abolished and a new card where Ubwoko referred to ethnic group was adopted. One could only be a Hutu, Tutsi or Twa.

So systematic was this change, that when asked, "Uri bwokoki?” one would quickly respond, "Ndi umuhutu, Ndi umututsi, Ndi umutwa”.

Rwandans could no longer identify themselves along clan lines, which cut across the Hutu, Tutsi, Twa divide and people who were once part of the same "family” became enemies overnight.

It is easier to kill an enemy

How was it possible to incite people to kill members of their clan when in past centuries, clans had fought together and conquered other clans? How were centuries of oral history erased so rapidly? How were ties broken so easily?

It started with limiting the number of groups people could associate with and demarcating right and wrong. In post-independence Rwanda, the "right” ethnic group became Hutu, the "wrong” ethnic group became Tutsi.

To reinforce this, the governments of Gregoire Kayibanda and Juvenal Habyarimana spread the idea originally found in colonial literature that said that Tutsis came from Abyssinia (Ethiopia), making them foreign invaders who oppressed indigenous, ‘legitimate’ Rwandans.

Kayibanda institutionalised the idea, using it for political ends. In this thinking, Tutsi meant foreign invader. Foreign meant enemy. Tutsi meant enemy.

During Kayibanda’s rule, Tutsis who had been exiled in 1959 attempted to return by force and widespread killings of Tutsi ensued. This "invasion” as it was called, meant Hutus could legitimately defend themselves against people who were once their kinsmen.

Ethnic differentiation led to discrimination, dehumanisation, political polarisation, eventually leading to the plan to exterminate the whole Tutsi group.

The Hutu manifesto, and later the Hutu Ten Commandments were about unifying the Hutu against its common enemy, the Tutsi.

Rwanda’s many clans and groupings, rich history and culture were effectively forgotten. It became a simple equation: Hutu – you live, Tutsi – you die.

Antoine Mugesera is a historian and retired Senator.